Deploying and Scaling Microservices

with Docker and Kubernetes

Self-paced version

A brief introduction

This was initially written by Jérôme Petazzoni to support in-person, instructor-led workshops and tutorials

Credit is also due to multiple contributors — thank you!

You can also follow along on your own, at your own pace

We included as much information as possible in these slides

We recommend having a mentor to help you ...

... Or be comfortable spending some time reading the Kubernetes documentation ...

... And looking for answers on StackOverflow and other outlets

Hands on, you shall practice

Nobody ever became a Jedi by spending their lives reading Wookiepedia

Likewise, it will take more than merely reading these slides to make you an expert

These slides include tons of exercises and examples

They assume that you have access to a Kubernetes cluster

If you are attending a workshop or tutorial:

you will be given specific instructions to access your clusterIf you are doing this on your own:

the first chapter will give you various options to get your own cluster

Accessing these slides now

We recommend that you open these slides in your browser:

Use arrows to move to next/previous slide

(up, down, left, right, page up, page down)

Type a slide number + ENTER to go to that slide

The slide number is also visible in the URL bar

(e.g. .../#123 for slide 123)

Accessing these slides later

Slides will remain online so you can review them later if needed

(let's say we'll keep them online at least 1 year, how about that?)

You can download the slides using that URL:

http://container.training/slides.zip

(then open the file

kube-selfpaced.yml.html)You will find new versions of these slides on:

These slides are open source

You are welcome to use, re-use, share these slides

These slides are written in markdown

The sources of these slides are available in a public GitHub repository:

Typos? Mistakes? Questions? Feel free to hover over the bottom of the slide ...

👇 Try it! The source file will be shown and you can view it on GitHub and fork and edit it.

Extra details

This slide has a little magnifying glass in the top left corner

This magnifying glass indicates slides that provide extra details

Feel free to skip them if:

you are in a hurry

you are new to this and want to avoid cognitive overload

you want only the most essential information

You can review these slides another time if you want, they'll be waiting for you ☺

Part 3

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 4

- Setting up Kubernetes

- Running a local development cluster

- Deploying a managed cluster

- Kubernetes distributions and installers

- The Kubernetes dashboard

- Security implications of

kubectl apply - k9s

- Tilt

- Scaling our demo app

- Daemon sets

- Labels and selectors

- Authoring YAML

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 6

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 7

- Exposing HTTP services with Ingress resources

- Ingress and TLS certificates

- cert-manager

- Kustomize

- Managing stacks with Helm

- Helm chart format

- Creating a basic chart

- Creating better Helm charts

- Charts using other charts

- Helm and invalid values

- Helm secrets

- CI/CD with GitLab

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 8

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 9

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 10

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 11

- Centralized logging

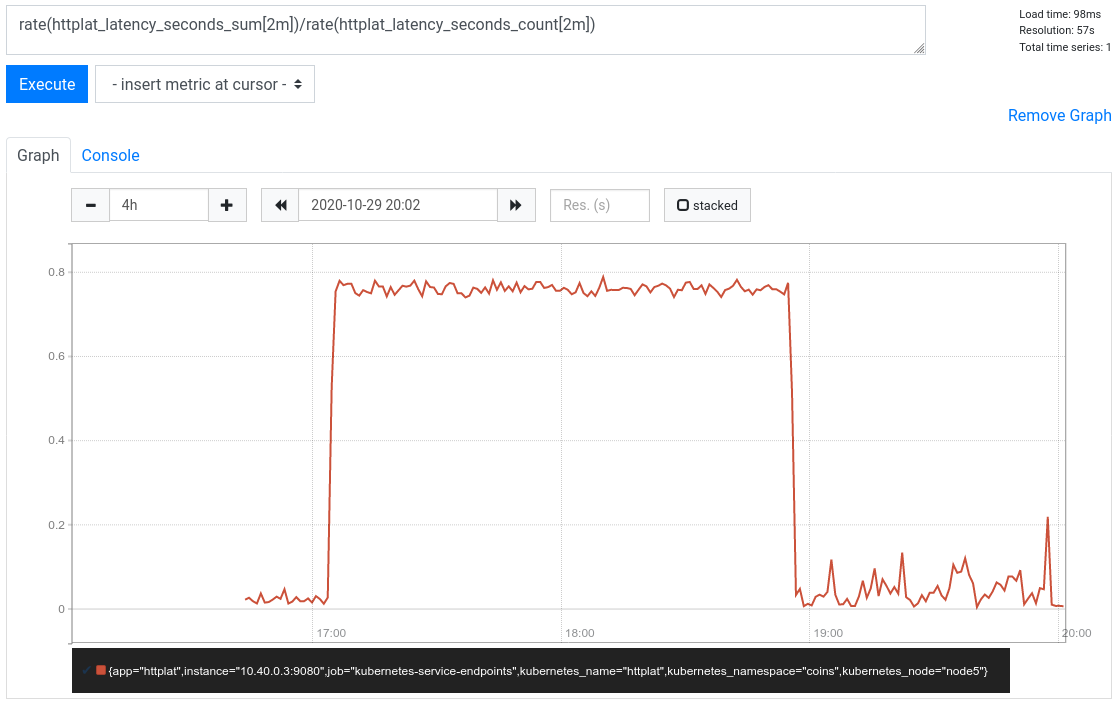

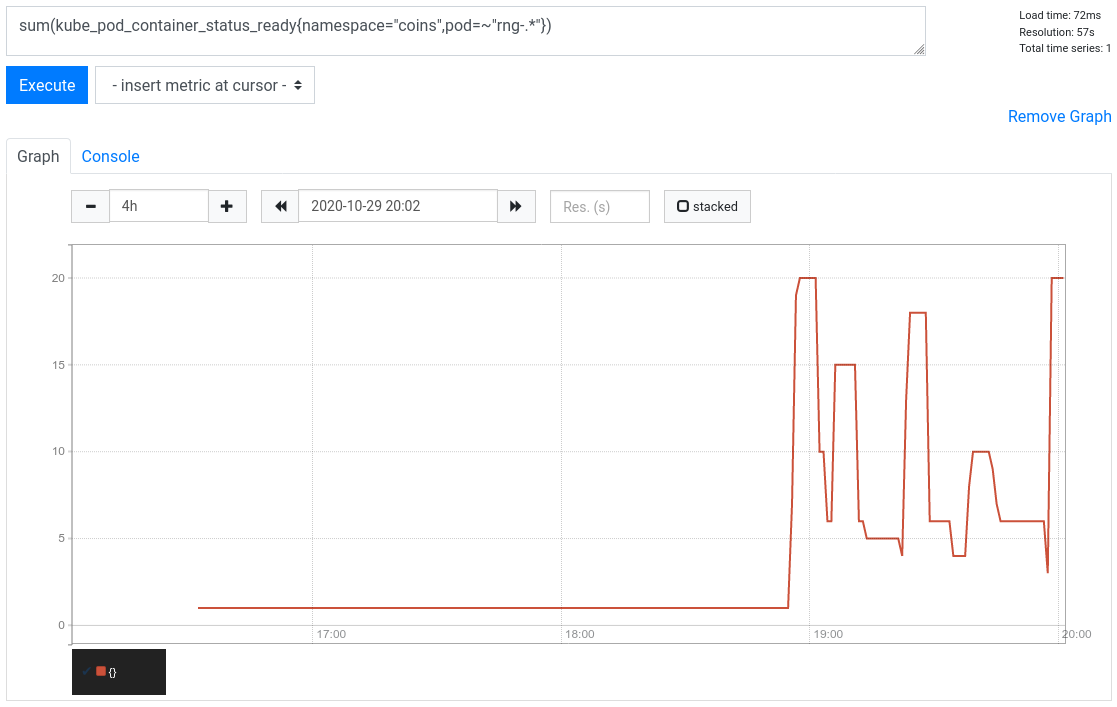

- Collecting metrics with Prometheus

- Prometheus and Grafana

- Resource Limits

- Defining min, max, and default resources

- Namespace quotas

- Limiting resources in practice

- Checking Node and Pod resource usage

- Cluster sizing

- The Horizontal Pod Autoscaler

- Scaling with custom metrics

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 12

- Extending the Kubernetes API

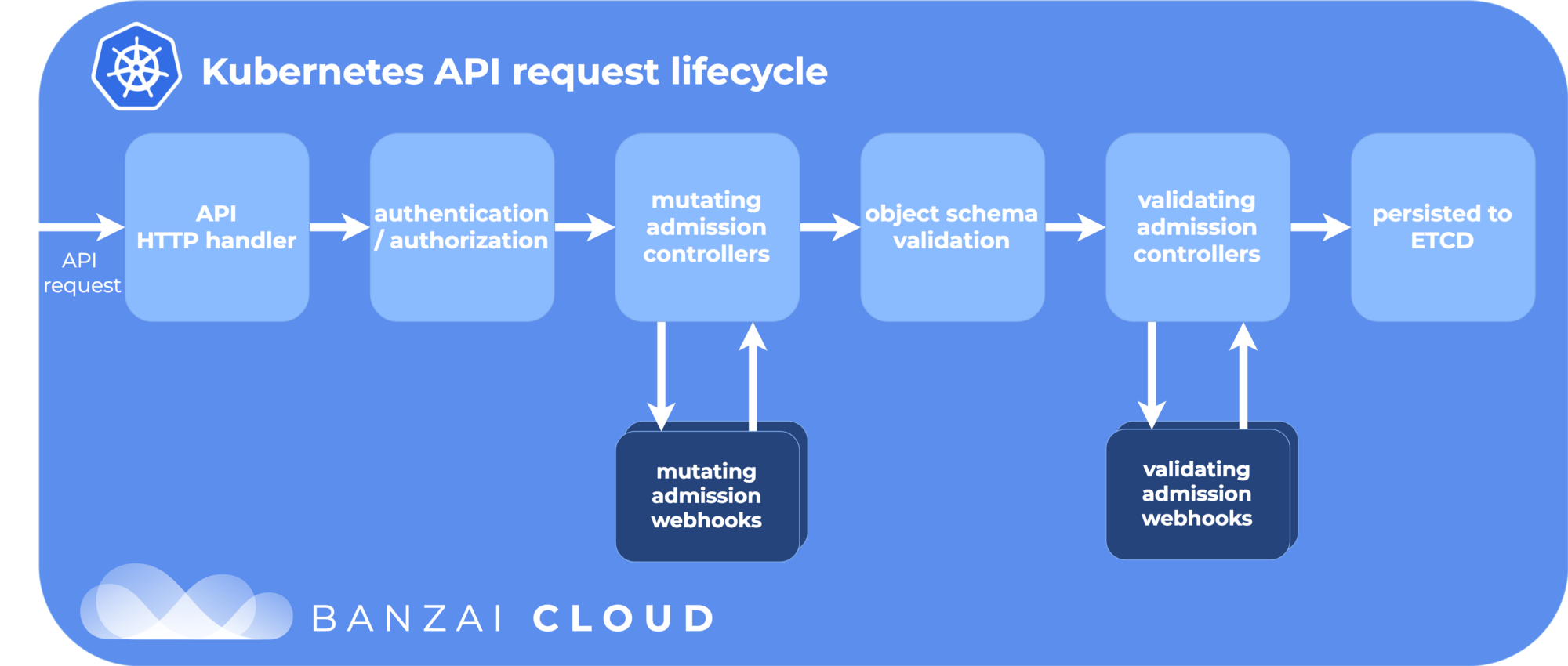

- API server internals

- Custom Resource Definitions

- The Aggregation Layer

- Dynamic Admission Control

- Operators

- Designing an operator

- Kubebuilder

- Sealed Secrets

- Policy Management with Kyverno

- An ElasticSearch Operator

- Finalizers

- Owners and dependents

- Events

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 13

(auto-generated TOC)

Part 14

(auto-generated TOC)

Pre-requirements

(automatically generated title slide)

Pre-requirements

Be comfortable with the UNIX command line

navigating directories

editing files

a little bit of bash-fu (environment variables, loops)

Some Docker knowledge

docker run,docker ps,docker buildideally, you know how to write a Dockerfile and build it

(even if it's aFROMline and a couple ofRUNcommands)

It's totally OK if you are not a Docker expert!

Tell me and I forget.

Teach me and I remember.

Involve me and I learn.

Misattributed to Benjamin Franklin

(Probably inspired by Chinese Confucian philosopher Xunzi)

Hands-on sections

The whole workshop is hands-on

We are going to build, ship, and run containers!

You are invited to reproduce all the demos

All hands-on sections are clearly identified, like the gray rectangle below

This is the stuff you're supposed to do!

Go to http://container.training/ to view these slides

Doing or re-doing the workshop on your own?

Use something like Play-With-Docker or Play-With-Kubernetes

Zero setup effort; but environment are short-lived and might have limited resources

Create your own cluster (local or cloud VMs)

Small setup effort; small cost; flexible environments

Create a bunch of clusters for you and your friends (instructions)

Bigger setup effort; ideal for group training

For a consistent Kubernetes experience ...

If you are using your own Kubernetes cluster, you can use shpod

shpodprovides a shell running in a pod on your own clusterIt comes with many tools pre-installed (helm, stern...)

These tools are used in many exercises in these slides

shpodalso gives you completion and a fancy prompt

Get your own Docker nodes

If you already have some Docker nodes: great!

If not: let's get some thanks to Play-With-Docker

Log in

Create your first node

You will need a Docker ID to use Play-With-Docker.

(Creating a Docker ID is free.)

We will (mostly) interact with node1 only

These remarks apply only when using multiple nodes, of course.

Unless instructed, all commands must be run from the first VM,

node1We will only check out/copy the code on

node1During normal operations, we do not need access to the other nodes

If we had to troubleshoot issues, we would use a combination of:

SSH (to access system logs, daemon status...)

Docker API (to check running containers and container engine status)

Terminals

Once in a while, the instructions will say:

"Open a new terminal."

There are multiple ways to do this:

create a new window or tab on your machine, and SSH into the VM;

use screen or tmux on the VM and open a new window from there.

You are welcome to use the method that you feel the most comfortable with.

Tmux cheatsheet

Tmux is a terminal multiplexer like screen.

You don't have to use it or even know about it to follow along.

But some of us like to use it to switch between terminals.

It has been preinstalled on your workshop nodes.

- Ctrl-b c → creates a new window

- Ctrl-b n → go to next window

- Ctrl-b p → go to previous window

- Ctrl-b " → split window top/bottom

- Ctrl-b % → split window left/right

- Ctrl-b Alt-1 → rearrange windows in columns

- Ctrl-b Alt-2 → rearrange windows in rows

- Ctrl-b arrows → navigate to other windows

- Ctrl-b d → detach session

- tmux attach → reattach to session

Versions installed

- Kubernetes 1.19.2

- Docker Engine 19.03.13

- Docker Compose 1.25.4

- Check all installed versions:kubectl versiondocker versiondocker-compose -v

Kubernetes and Docker compatibility

Kubernetes 1.17 validates Docker Engine version up to 19.03

however ...

Kubernetes 1.15 validates Docker Engine versions up to 18.09

(the latest version when Kubernetes 1.14 was released)Kubernetes 1.13 only validates Docker Engine versions up to 18.06

Is it a problem if I use Kubernetes with a "too recent" Docker Engine?

Kubernetes and Docker compatibility

Kubernetes 1.17 validates Docker Engine version up to 19.03

however ...

Kubernetes 1.15 validates Docker Engine versions up to 18.09

(the latest version when Kubernetes 1.14 was released)Kubernetes 1.13 only validates Docker Engine versions up to 18.06

Is it a problem if I use Kubernetes with a "too recent" Docker Engine?

No!

"Validates" = continuous integration builds with very extensive (and expensive) testing

The Docker API is versioned, and offers strong backward-compatibility

(if a client uses e.g. API v1.25, the Docker Engine will keep behaving the same way)

Kubernetes versioning and cadence

Kubernetes versions are expressed using semantic versioning

(a Kubernetes version is expressed as MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH)

There is a new patch release whenever needed

(generally, there is about 2 to 4 weeks between patch releases, except when a critical bug or vulnerability is found: in that case, a patch release will follow as fast as possible)

There is a new minor release approximately every 3 months

At any given time, 3 minor releases are maintained

(in other words, a given minor release is maintained about 9 months)

Kubernetes version compatibility

Should my version of kubectl match exactly my cluster version?

kubectlcan be up to one minor version older or newer than the cluster(if cluster version is 1.15.X,

kubectlcan be 1.14.Y, 1.15.Y, or 1.16.Y)Things might work with larger version differences

(but they will probably fail randomly, so be careful)

This is an example of an error indicating version compability issues:

error: SchemaError(io.k8s.api.autoscaling.v2beta1.ExternalMetricStatus):invalid object doesn't have additional propertiesCheck the documentation for the whole story about compatibility

:EN:- Kubernetes versioning and compatibility :FR:- Les versions de Kubernetes et leur compatibilité

Our sample application

(automatically generated title slide)

Our sample application

We will clone the GitHub repository onto our

node1The repository also contains scripts and tools that we will use through the workshop

- Clone the repository on

node1:git clone https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training

(You can also fork the repository on GitHub and clone your fork if you prefer that.)

Downloading and running the application

Let's start this before we look around, as downloading will take a little time...

Go to the

dockercoinsdirectory, in the cloned repo:cd ~/container.training/dockercoinsUse Compose to build and run all containers:

docker-compose up

Compose tells Docker to build all container images (pulling the corresponding base images), then starts all containers, and displays aggregated logs.

What's this application?

What's this application?

- It is a DockerCoin miner! 💰🐳📦🚢

What's this application?

It is a DockerCoin miner! 💰🐳📦🚢

No, you can't buy coffee with DockerCoins

What's this application?

It is a DockerCoin miner! 💰🐳📦🚢

No, you can't buy coffee with DockerCoins

How DockerCoins works:

generate a few random bytes

hash these bytes

increment a counter (to keep track of speed)

repeat forever!

What's this application?

It is a DockerCoin miner! 💰🐳📦🚢

No, you can't buy coffee with DockerCoins

How DockerCoins works:

generate a few random bytes

hash these bytes

increment a counter (to keep track of speed)

repeat forever!

DockerCoins is not a cryptocurrency

(the only common points are "randomness," "hashing," and "coins" in the name)

DockerCoins in the microservices era

DockerCoins is made of 5 services:

rng= web service generating random byteshasher= web service computing hash of POSTed dataworker= background process callingrngandhasherwebui= web interface to watch progressredis= data store (holds a counter updated byworker)

These 5 services are visible in the application's Compose file, docker-compose.yml

How DockerCoins works

workerinvokes web servicerngto generate random bytesworkerinvokes web servicehasherto hash these bytesworkerdoes this in an infinite loopevery second,

workerupdatesredisto indicate how many loops were donewebuiqueriesredis, and computes and exposes "hashing speed" in our browser

(See diagram on next slide!)

Service discovery in container-land

How does each service find out the address of the other ones?

Service discovery in container-land

How does each service find out the address of the other ones?

We do not hard-code IP addresses in the code

We do not hard-code FQDNs in the code, either

We just connect to a service name, and container-magic does the rest

(And by container-magic, we mean "a crafty, dynamic, embedded DNS server")

Example in worker/worker.py

redis = Redis("redis")def get_random_bytes(): r = requests.get("http://rng/32") return r.contentdef hash_bytes(data): r = requests.post("http://hasher/", data=data, headers={"Content-Type": "application/octet-stream"})(Full source code available here)

Links, naming, and service discovery

Containers can have network aliases (resolvable through DNS)

Compose file version 2+ makes each container reachable through its service name

Compose file version 1 required "links" sections to accomplish this

Network aliases are automatically namespaced

you can have multiple apps declaring and using a service named

databasecontainers in the blue app will resolve

databaseto the IP of the blue databasecontainers in the green app will resolve

databaseto the IP of the green database

Show me the code!

You can check the GitHub repository with all the materials of this workshop:

https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.trainingThe application is in the dockercoins subdirectory

The Compose file (docker-compose.yml) lists all 5 services

redisis using an official image from the Docker Hubhasher,rng,worker,webuiare each built from a DockerfileEach service's Dockerfile and source code is in its own directory

(

hasheris in the hasher directory,rngis in the rng directory, etc.)

Compose file format version

This is relevant only if you have used Compose before 2016...

Compose 1.6 introduced support for a new Compose file format (aka "v2")

Services are no longer at the top level, but under a

servicessectionThere has to be a

versionkey at the top level, with value"2"(as a string, not an integer)Containers are placed on a dedicated network, making links unnecessary

There are other minor differences, but upgrade is easy and straightforward

Our application at work

On the left-hand side, the "rainbow strip" shows the container names

On the right-hand side, we see the output of our containers

We can see the

workerservice making requests torngandhasherFor

rngandhasher, we see HTTP access logs

Connecting to the web UI

"Logs are exciting and fun!" (No-one, ever)

The

webuicontainer exposes a web dashboard; let's view it

With a web browser, connect to

node1on port 8000Remember: the

nodeXaliases are valid only on the nodes themselvesIn your browser, you need to enter the IP address of your node

A drawing area should show up, and after a few seconds, a blue graph will appear.

If the graph doesn't load

If you just see a Page not found error, it might be because your

Docker Engine is running on a different machine. This can be the case if:

you are using the Docker Toolbox

you are using a VM (local or remote) created with Docker Machine

you are controlling a remote Docker Engine

When you run DockerCoins in development mode, the web UI static files are mapped to the container using a volume. Alas, volumes can only work on a local environment, or when using Docker Desktop for Mac or Windows.

How to fix this?

Stop the app with ^C, edit dockercoins.yml, comment out the volumes section, and try again.

Why does the speed seem irregular?

It looks like the speed is approximately 4 hashes/second

Or more precisely: 4 hashes/second, with regular dips down to zero

Why?

Why does the speed seem irregular?

It looks like the speed is approximately 4 hashes/second

Or more precisely: 4 hashes/second, with regular dips down to zero

Why?

The app actually has a constant, steady speed: 3.33 hashes/second

(which corresponds to 1 hash every 0.3 seconds, for reasons)Yes, and?

The reason why this graph is not awesome

The worker doesn't update the counter after every loop, but up to once per second

The speed is computed by the browser, checking the counter about once per second

Between two consecutive updates, the counter will increase either by 4, or by 0

The perceived speed will therefore be 4 - 4 - 4 - 0 - 4 - 4 - 0 etc.

What can we conclude from this?

The reason why this graph is not awesome

The worker doesn't update the counter after every loop, but up to once per second

The speed is computed by the browser, checking the counter about once per second

Between two consecutive updates, the counter will increase either by 4, or by 0

The perceived speed will therefore be 4 - 4 - 4 - 0 - 4 - 4 - 0 etc.

What can we conclude from this?

- "I'm clearly incapable of writing good frontend code!" 😀 — Jérôme

Stopping the application

If we interrupt Compose (with

^C), it will politely ask the Docker Engine to stop the appThe Docker Engine will send a

TERMsignal to the containersIf the containers do not exit in a timely manner, the Engine sends a

KILLsignal

- Stop the application by hitting

^C

Stopping the application

If we interrupt Compose (with

^C), it will politely ask the Docker Engine to stop the appThe Docker Engine will send a

TERMsignal to the containersIf the containers do not exit in a timely manner, the Engine sends a

KILLsignal

- Stop the application by hitting

^C

Some containers exit immediately, others take longer.

The containers that do not handle SIGTERM end up being killed after a 10s timeout. If we are very impatient, we can hit ^C a second time!

Clean up

- Before moving on, let's remove those containers

- Tell Compose to remove everything:docker-compose down

Kubernetes concepts

(automatically generated title slide)

Kubernetes concepts

Kubernetes is a container management system

It runs and manages containerized applications on a cluster

Kubernetes concepts

Kubernetes is a container management system

It runs and manages containerized applications on a cluster

What does that really mean?

What can we do with Kubernetes?

Let's imagine that we have a 3-tier e-commerce app:

web frontend

API backend

database (that we will keep out of Kubernetes for now)

We have built images for our frontend and backend components

(e.g. with Dockerfiles and

docker build)We are running them successfully with a local environment

(e.g. with Docker Compose)

Let's see how we would deploy our app on Kubernetes!

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

- Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers

Start 10 containers using image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers

Start 10 containers using image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Place a public load balancer in front of these containers

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers

Start 10 containers using image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Place a public load balancer in front of these containers

It's Black Friday (or Christmas), traffic spikes, grow our cluster and add containers

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers

Start 10 containers using image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Place a public load balancer in front of these containers

It's Black Friday (or Christmas), traffic spikes, grow our cluster and add containers

New release! Replace my containers with the new image

atseashop/webfront:v1.4

Basic things we can ask Kubernetes to do

Start 5 containers using image

atseashop/api:v1.3Place an internal load balancer in front of these containers

Start 10 containers using image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Place a public load balancer in front of these containers

It's Black Friday (or Christmas), traffic spikes, grow our cluster and add containers

New release! Replace my containers with the new image

atseashop/webfront:v1.4Keep processing requests during the upgrade; update my containers one at a time

Other things that Kubernetes can do for us

Autoscaling

(straightforward on CPU; more complex on other metrics)

Resource management and scheduling

(reserve CPU/RAM for containers; placement constraints)

Advanced rollout patterns

(blue/green deployment, canary deployment)

More things that Kubernetes can do for us

Batch jobs

(one-off; parallel; also cron-style periodic execution)

Fine-grained access control

(defining what can be done by whom on which resources)

Stateful services

(databases, message queues, etc.)

Automating complex tasks with operators

(e.g. database replication, failover, etc.)

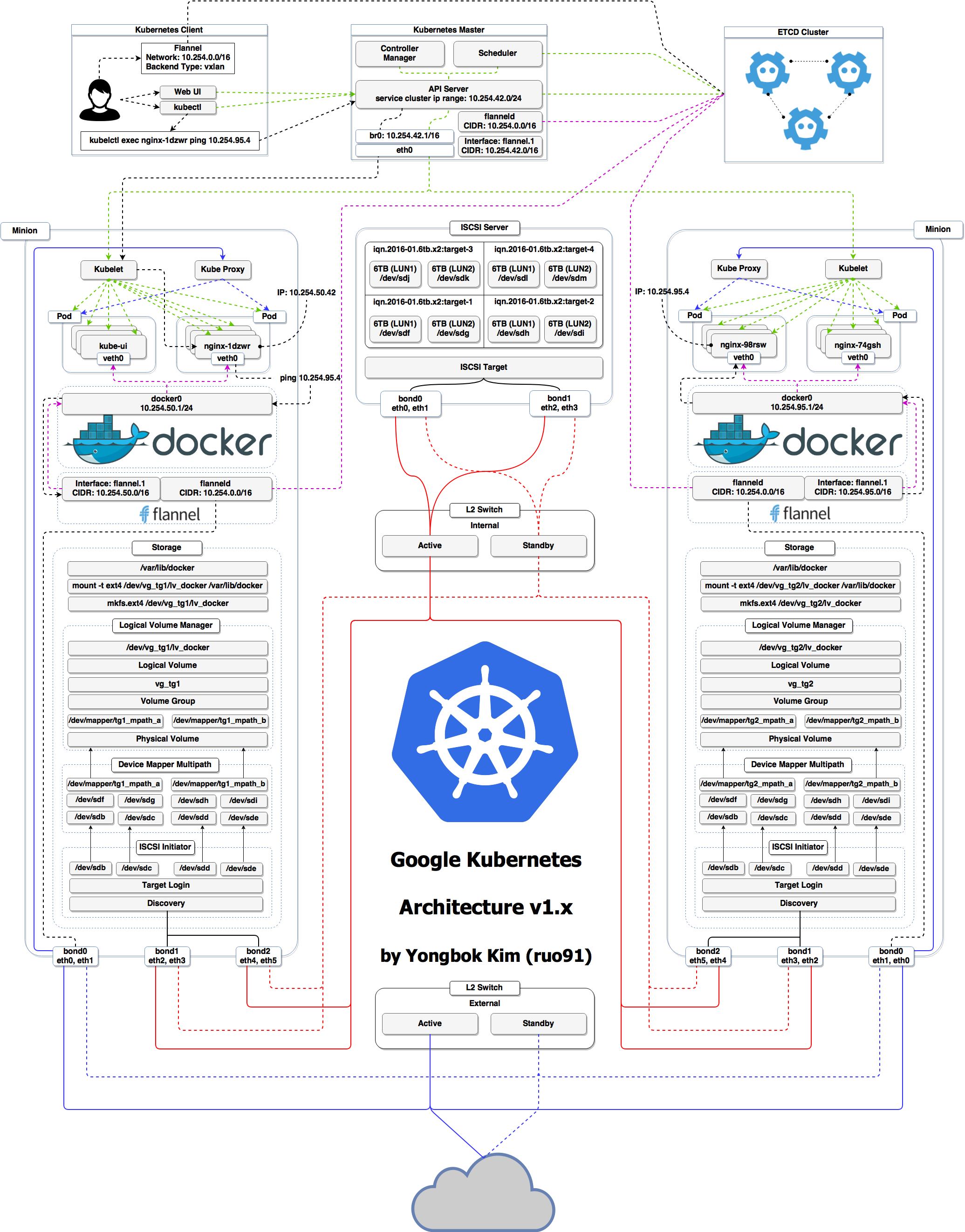

Kubernetes architecture

Ha ha ha ha

OK, I was trying to scare you, it's much simpler than that ❤️

Credits

The first schema is a Kubernetes cluster with storage backed by multi-path iSCSI

(Courtesy of Yongbok Kim)

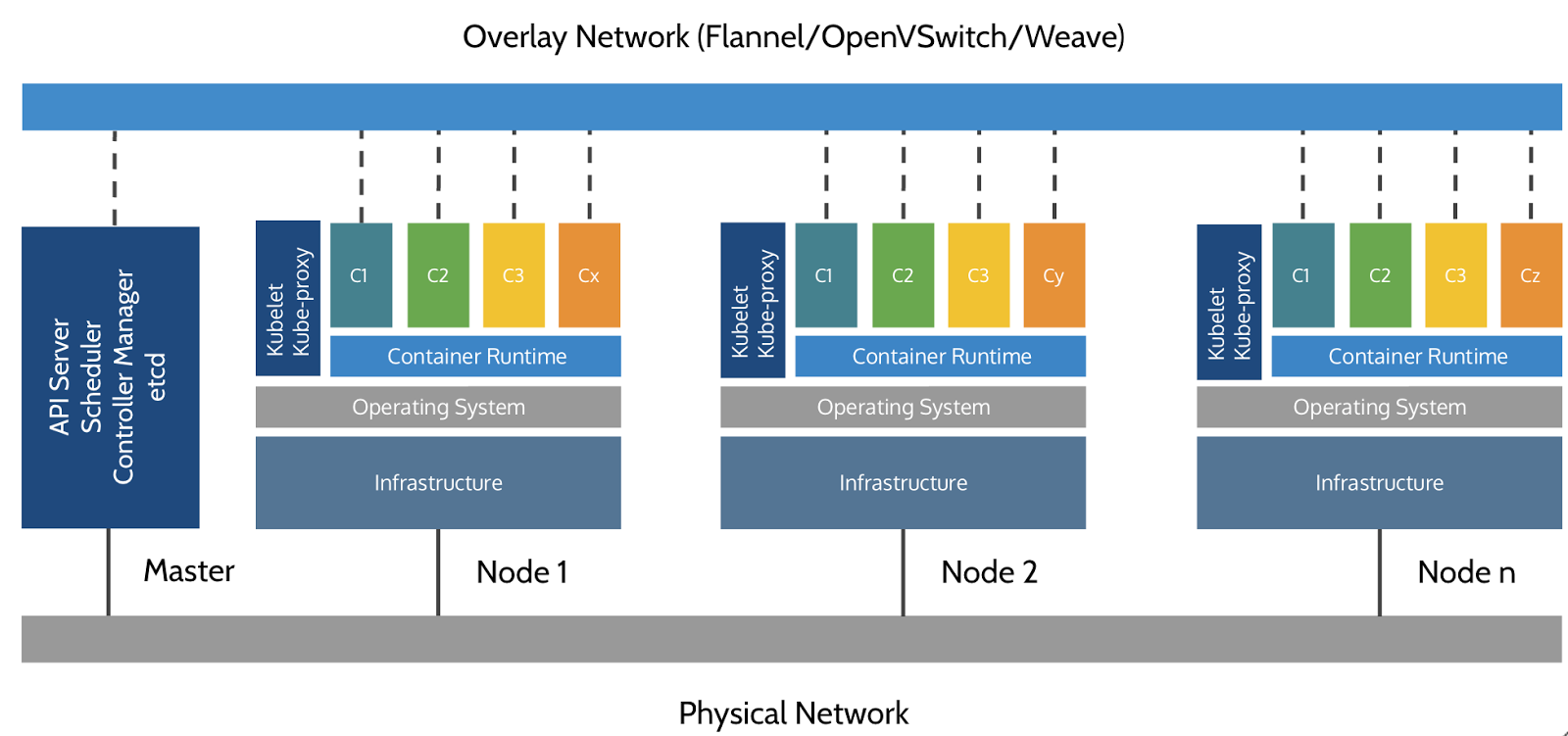

The second one is a simplified representation of a Kubernetes cluster

(Courtesy of Imesh Gunaratne)

Kubernetes architecture: the nodes

The nodes executing our containers run a collection of services:

a container Engine (typically Docker)

kubelet (the "node agent")

kube-proxy (a necessary but not sufficient network component)

Nodes were formerly called "minions"

(You might see that word in older articles or documentation)

Kubernetes architecture: the control plane

The Kubernetes logic (its "brains") is a collection of services:

the API server (our point of entry to everything!)

core services like the scheduler and controller manager

etcd(a highly available key/value store; the "database" of Kubernetes)

Together, these services form the control plane of our cluster

The control plane is also called the "master"

Running the control plane on special nodes

It is common to reserve a dedicated node for the control plane

(Except for single-node development clusters, like when using minikube)

This node is then called a "master"

(Yes, this is ambiguous: is the "master" a node, or the whole control plane?)

Normal applications are restricted from running on this node

(By using a mechanism called "taints")

When high availability is required, each service of the control plane must be resilient

The control plane is then replicated on multiple nodes

(This is sometimes called a "multi-master" setup)

Running the control plane outside containers

The services of the control plane can run in or out of containers

For instance: since

etcdis a critical service, some people deploy it directly on a dedicated cluster (without containers)(This is illustrated on the first "super complicated" schema)

In some hosted Kubernetes offerings (e.g. AKS, GKE, EKS), the control plane is invisible

(We only "see" a Kubernetes API endpoint)

In that case, there is no "master node"

For this reason, it is more accurate to say "control plane" rather than "master."

How many nodes should a cluster have?

There is no particular constraint

(no need to have an odd number of nodes for quorum)

A cluster can have zero node

(but then it won't be able to start any pods)

For testing and development, having a single node is fine

For production, make sure that you have extra capacity

(so that your workload still fits if you lose a node or a group of nodes)

Kubernetes is tested with up to 5000 nodes

(however, running a cluster of that size requires a lot of tuning)

Do we need to run Docker at all?

No!

Do we need to run Docker at all?

No!

By default, Kubernetes uses the Docker Engine to run containers

We can leverage other pluggable runtimes through the Container Runtime Interface

We could also use(deprecated)rkt("Rocket") from CoreOS

Some runtimes available through CRI

-

- maintained by Docker, IBM, and community

- used by Docker Engine, microk8s, k3s, GKE; also standalone

- comes with its own CLI,

ctr

-

- maintained by Red Hat, SUSE, and community

- used by OpenShift and Kubic

- designed specifically as a minimal runtime for Kubernetes

Do we need to run Docker at all?

Yes!

Do we need to run Docker at all?

Yes!

In this workshop, we run our app on a single node first

We will need to build images and ship them around

We can do these things without Docker

(and get diagnosed with NIH¹ syndrome)Docker is still the most stable container engine today

(but other options are maturing very quickly)

Do we need to run Docker at all?

On our development environments, CI pipelines ... :

Yes, almost certainly

On our production servers:

Yes (today)

Probably not (in the future)

More information about CRI on the Kubernetes blog

Interacting with Kubernetes

We will interact with our Kubernetes cluster through the Kubernetes API

The Kubernetes API is (mostly) RESTful

It allows us to create, read, update, delete resources

A few common resource types are:

node (a machine — physical or virtual — in our cluster)

pod (group of containers running together on a node)

service (stable network endpoint to connect to one or multiple containers)

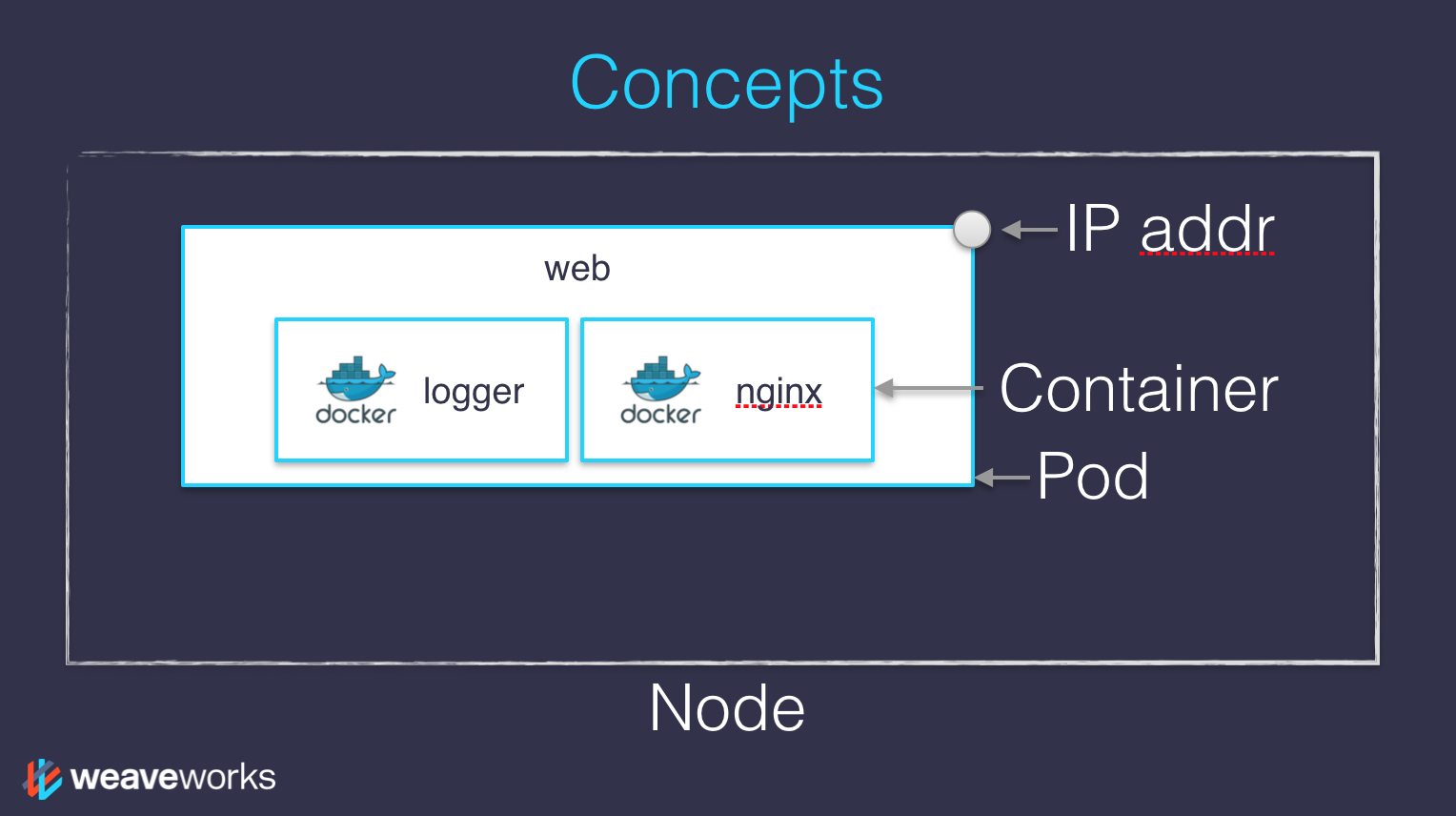

Scaling

How would we scale the pod shown on the previous slide?

Do create additional pods

each pod can be on a different node

each pod will have its own IP address

Do not add more NGINX containers in the pod

all the NGINX containers would be on the same node

they would all have the same IP address

(resulting inAddress alreading in useerrors)

Together or separate

Should we put e.g. a web application server and a cache together?

("cache" being something like e.g. Memcached or Redis)Putting them in the same pod means:

they have to be scaled together

they can communicate very efficiently over

localhost

Putting them in different pods means:

they can be scaled separately

they must communicate over remote IP addresses

(incurring more latency, lower performance)

Both scenarios can make sense, depending on our goals

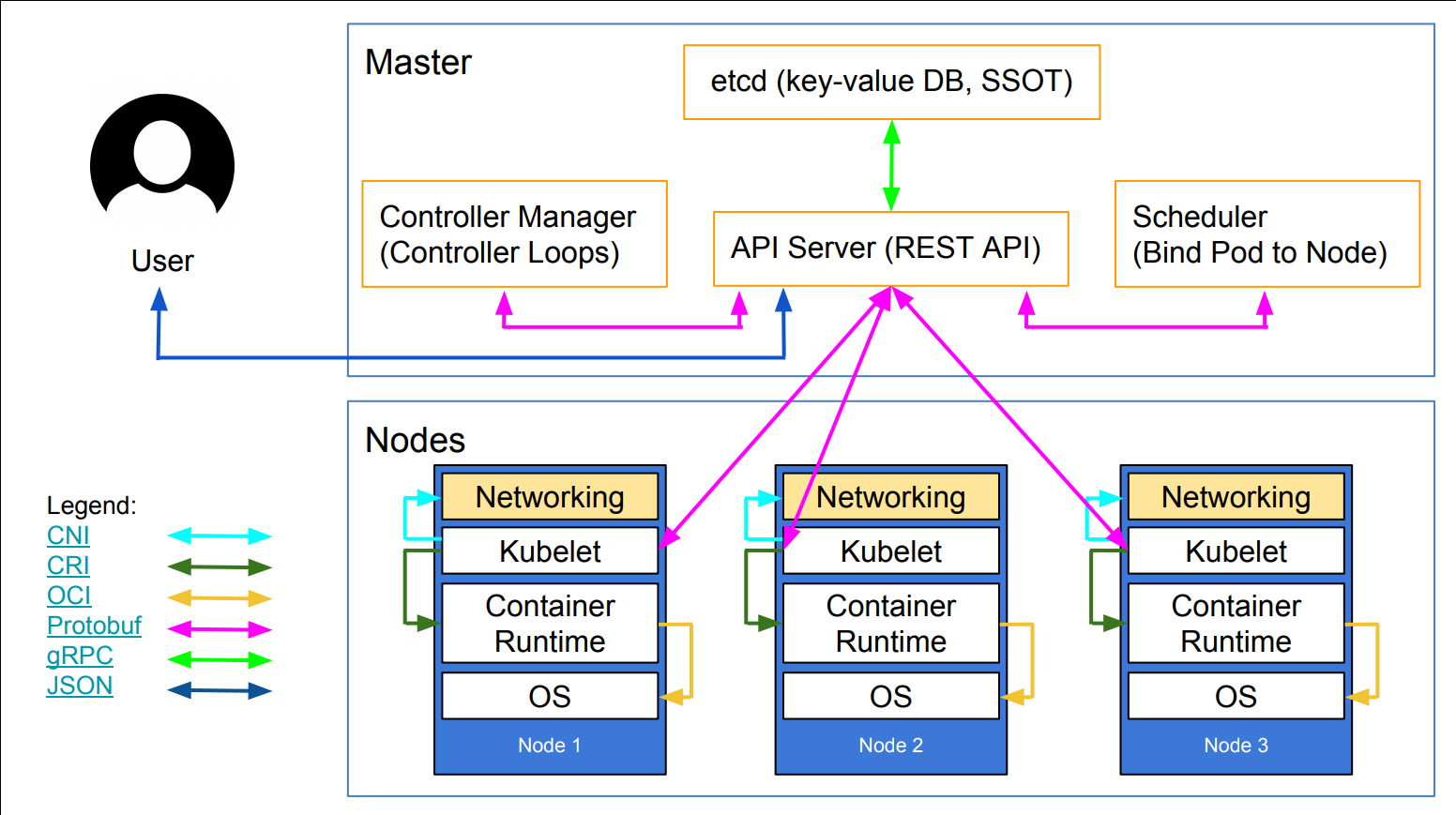

Credits

The first diagram is courtesy of Lucas Käldström, in this presentation

- it's one of the best Kubernetes architecture diagrams available!

The second diagram is courtesy of Weave Works

a pod can have multiple containers working together

IP addresses are associated with pods, not with individual containers

Both diagrams used with permission.

:EN:- Kubernetes concepts :FR:- Kubernetes en théorie

First contact with kubectl

(automatically generated title slide)

First contact with kubectl

kubectlis (almost) the only tool we'll need to talk to KubernetesIt is a rich CLI tool around the Kubernetes API

(Everything you can do with

kubectl, you can do directly with the API)On our machines, there is a

~/.kube/configfile with:the Kubernetes API address

the path to our TLS certificates used to authenticate

You can also use the

--kubeconfigflag to pass a config fileOr directly

--server,--user, etc.kubectlcan be pronounced "Cube C T L", "Cube cuttle", "Cube cuddle"...

kubectl is the new SSH

We often start managing servers with SSH

(installing packages, troubleshooting ...)

At scale, it becomes tedious, repetitive, error-prone

Instead, we use config management, central logging, etc.

In many cases, we still need SSH:

as the underlying access method (e.g. Ansible)

to debug tricky scenarios

to inspect and poke at things

The parallel with kubectl

We often start managing Kubernetes clusters with

kubectl(deploying applications, troubleshooting ...)

At scale (with many applications or clusters), it becomes tedious, repetitive, error-prone

Instead, we use automated pipelines, observability tooling, etc.

In many cases, we still need

kubectl:to debug tricky scenarios

to inspect and poke at things

The Kubernetes API is always the underlying access method

kubectl get

- Let's look at our

Noderesources withkubectl get!

Look at the composition of our cluster:

kubectl get nodeThese commands are equivalent:

kubectl get nokubectl get nodekubectl get nodes

Obtaining machine-readable output

kubectl getcan output JSON, YAML, or be directly formatted

Give us more info about the nodes:

kubectl get nodes -o wideLet's have some YAML:

kubectl get no -o yamlSee that

kind: Listat the end? It's the type of our result!

(Ab)using kubectl and jq

- It's super easy to build custom reports

- Show the capacity of all our nodes as a stream of JSON objects:kubectl get nodes -o json |jq ".items[] | {name:.metadata.name} + .status.capacity"

Exploring types and definitions

We can list all available resource types by running

kubectl api-resources

(In Kubernetes 1.10 and prior, this command used to bekubectl get)We can view the definition for a resource type with:

kubectl explain typeWe can view the definition of a field in a resource, for instance:

kubectl explain node.specOr get the full definition of all fields and sub-fields:

kubectl explain node --recursive

Introspection vs. documentation

We can access the same information by reading the API documentation

The API documentation is usually easier to read, but:

it won't show custom types (like Custom Resource Definitions)

we need to make sure that we look at the correct version

kubectl api-resourcesandkubectl explainperform introspection(they communicate with the API server and obtain the exact type definitions)

Type names

The most common resource names have three forms:

singular (e.g.

node,service,deployment)plural (e.g.

nodes,services,deployments)short (e.g.

no,svc,deploy)

Some resources do not have a short name

Endpointsonly have a plural form(because even a single

Endpointsresource is actually a list of endpoints)

Viewing details

We can use

kubectl get -o yamlto see all available detailsHowever, YAML output is often simultaneously too much and not enough

For instance,

kubectl get node node1 -o yamlis:too much information (e.g.: list of images available on this node)

not enough information (e.g.: doesn't show pods running on this node)

difficult to read for a human operator

For a comprehensive overview, we can use

kubectl describeinstead

kubectl describe

kubectl describeneeds a resource type and (optionally) a resource nameIt is possible to provide a resource name prefix

(all matching objects will be displayed)

kubectl describewill retrieve some extra information about the resource

- Look at the information available for

node1with one of the following commands:kubectl describe node/node1kubectl describe node node1

(We should notice a bunch of control plane pods.)

Listing running containers

Containers are manipulated through pods

A pod is a group of containers:

running together (on the same node)

sharing resources (RAM, CPU; but also network, volumes)

- List pods on our cluster:kubectl get pods

Listing running containers

Containers are manipulated through pods

A pod is a group of containers:

running together (on the same node)

sharing resources (RAM, CPU; but also network, volumes)

- List pods on our cluster:kubectl get pods

Where are the pods that we saw just a moment earlier?!?

Namespaces

- Namespaces allow us to segregate resources

- List the namespaces on our cluster with one of these commands:kubectl get namespaceskubectl get namespacekubectl get ns

Namespaces

- Namespaces allow us to segregate resources

- List the namespaces on our cluster with one of these commands:kubectl get namespaceskubectl get namespacekubectl get ns

You know what ... This kube-system thing looks suspicious.

In fact, I'm pretty sure it showed up earlier, when we did:

kubectl describe node node1

Accessing namespaces

By default,

kubectluses thedefaultnamespaceWe can see resources in all namespaces with

--all-namespaces

List the pods in all namespaces:

kubectl get pods --all-namespacesSince Kubernetes 1.14, we can also use

-Aas a shorter version:kubectl get pods -A

Here are our system pods!

What are all these control plane pods?

etcdis our etcd serverkube-apiserveris the API serverkube-controller-managerandkube-schedulerare other control plane componentscorednsprovides DNS-based service discovery (replacing kube-dns as of 1.11)kube-proxyis the (per-node) component managing port mappings and suchweaveis the (per-node) component managing the network overlaythe

READYcolumn indicates the number of containers in each pod(1 for most pods, but

weavehas 2, for instance)

Scoping another namespace

- We can also look at a different namespace (other than

default)

- List only the pods in the

kube-systemnamespace:kubectl get pods --namespace=kube-systemkubectl get pods -n kube-system

Namespaces and other kubectl commands

We can use

-n/--namespacewith almost everykubectlcommandExample:

kubectl create --namespace=Xto create something in namespace X

We can use

-A/--all-namespaceswith most commands that manipulate multiple objectsExamples:

kubectl deletecan delete resources across multiple namespaceskubectl labelcan add/remove/update labels across multiple namespaces

What about kube-public?

- List the pods in the

kube-publicnamespace:kubectl -n kube-public get pods

Nothing!

kube-public is created by kubeadm & used for security bootstrapping.

Exploring kube-public

- The only interesting object in

kube-publicis a ConfigMap namedcluster-info

List ConfigMap objects:

kubectl -n kube-public get configmapsInspect

cluster-info:kubectl -n kube-public get configmap cluster-info -o yaml

Note the selfLink URI: /api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info

We can use that!

Accessing cluster-info

Earlier, when trying to access the API server, we got a

ForbiddenmessageBut

cluster-infois readable by everyone (even without authentication)

- Retrieve

cluster-info:curl -k https://10.96.0.1/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info

We were able to access

cluster-info(without auth)It contains a

kubeconfigfile

Retrieving kubeconfig

- We can easily extract the

kubeconfigfile from this ConfigMap

- Display the content of

kubeconfig:curl -sk https://10.96.0.1/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info \| jq -r .data.kubeconfig

This file holds the canonical address of the API server, and the public key of the CA

This file does not hold client keys or tokens

This is not sensitive information, but allows us to establish trust

What about kube-node-lease?

Starting with Kubernetes 1.14, there is a

kube-node-leasenamespace(or in Kubernetes 1.13 if the NodeLease feature gate is enabled)

That namespace contains one Lease object per node

Node leases are a new way to implement node heartbeats

(i.e. node regularly pinging the control plane to say "I'm alive!")

For more details, see KEP-0009 or the node controller documentation k8s/kubectlget.md

Services

A service is a stable endpoint to connect to "something"

(In the initial proposal, they were called "portals")

- List the services on our cluster with one of these commands:kubectl get serviceskubectl get svc

Services

A service is a stable endpoint to connect to "something"

(In the initial proposal, they were called "portals")

- List the services on our cluster with one of these commands:kubectl get serviceskubectl get svc

There is already one service on our cluster: the Kubernetes API itself.

ClusterIP services

A

ClusterIPservice is internal, available from the cluster onlyThis is useful for introspection from within containers

Try to connect to the API:

curl -k https://10.96.0.1-kis used to skip certificate verificationMake sure to replace 10.96.0.1 with the CLUSTER-IP shown by

kubectl get svc

The command above should either time out, or show an authentication error. Why?

Time out

Connections to ClusterIP services only work from within the cluster

If we are outside the cluster, the

curlcommand will probably time out(Because the IP address, e.g. 10.96.0.1, isn't routed properly outside the cluster)

This is the case with most "real" Kubernetes clusters

To try the connection from within the cluster, we can use shpod

Authentication error

This is what we should see when connecting from within the cluster:

$ curl -k https://10.96.0.1{ "kind": "Status", "apiVersion": "v1", "metadata": { }, "status": "Failure", "message": "forbidden: User \"system:anonymous\" cannot get path \"/\"", "reason": "Forbidden", "details": { }, "code": 403}Explanations

We can see

kind,apiVersion,metadataThese are typical of a Kubernetes API reply

Because we are talking to the Kubernetes API

The Kubernetes API tells us "Forbidden"

(because it requires authentication)

The Kubernetes API is reachable from within the cluster

(many apps integrating with Kubernetes will use this)

DNS integration

Each service also gets a DNS record

The Kubernetes DNS resolver is available from within pods

(and sometimes, from within nodes, depending on configuration)

Code running in pods can connect to services using their name

(e.g. https://kubernetes/...)

:EN:- Getting started with kubectl :FR:- Se familiariser avec kubectl

Running our first containers on Kubernetes

(automatically generated title slide)

Running our first containers on Kubernetes

- First things first: we cannot run a container

Running our first containers on Kubernetes

First things first: we cannot run a container

We are going to run a pod, and in that pod there will be a single container

Running our first containers on Kubernetes

First things first: we cannot run a container

We are going to run a pod, and in that pod there will be a single container

In that container in the pod, we are going to run a simple

pingcommand

Running our first containers on Kubernetes

First things first: we cannot run a container

We are going to run a pod, and in that pod there will be a single container

In that container in the pod, we are going to run a simple

pingcommandSounds simple enough, right?

Running our first containers on Kubernetes

First things first: we cannot run a container

We are going to run a pod, and in that pod there will be a single container

In that container in the pod, we are going to run a simple

pingcommandSounds simple enough, right?

Except ... that the

kubectl runcommand changed in Kubernetes 1.18!We'll explain what has changed, and why

Choose your own adventure

- First, let's check which version of Kubernetes we're running

Check our API server version:

kubectl versionLook at the Server Version in the second part of the output

In the following slides, we will talk about 1.17- or 1.18+

(to indicate "up to Kubernetes 1.17" and "from Kubernetes 1.18")

Starting a simple pod with kubectl run

kubectl runis convenient to start a single podWe need to specify at least a name and the image we want to use

Optionally, we can specify the command to run in the pod

- Let's ping the address of

localhost, the loopback interface:kubectl run pingpong --image alpine ping 127.0.0.1

What do we see?

In Kubernetes 1.18+, the output tells us that a Pod is created:

pod/pingpong createdIn Kubernetes 1.17-, the output is much more verbose:

kubectl run --generator=deployment/apps.v1 is DEPRECATEDand will be removed in a future version. Use kubectl run--generator=run-pod/v1 or kubectl create instead.deployment.apps/pingpong createdThere is a deprecation warning ...

... And a Deployment was created instead of a Pod

🤔 What does that mean?

Show me all you got!

- What resources were created by

kubectl run?

- Let's ask Kubernetes to show us all the resources:kubectl get all

Note: kubectl get all is a lie. It doesn't show everything.

(But it shows a lot of "usual suspects", i.e. commonly used resources.)

The situation with Kubernetes 1.18+

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGEpod/pingpong 1/1 Running 0 9sNAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGEservice/kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 3h30mWe wanted a pod, we got a pod, named pingpong. Great!

(We can ignore service/kubernetes, it was already there before.)

The situation with Kubernetes 1.17-

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGEpod/pingpong-6ccbc77f68-kmgfn 1/1 Running 0 11sNAME TYPE CLUSTER-IP EXTERNAL-IP PORT(S) AGEservice/kubernetes ClusterIP 10.96.0.1 <none> 443/TCP 3h45NAME READY UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGEdeployment.apps/pingpong 1/1 1 1 11sNAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGEreplicaset.apps/pingpong-6ccbc77f68 1 1 1 11sOur pod is not named pingpong, but pingpong-xxxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy.

We have a Deployment named pingpong, and an extra Replica Set, too. What's going on?

From Deployment to Pod

We have the following resources:

deployment.apps/pingpongThis is the Deployment that we just created.

replicaset.apps/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxxThis is a Replica Set created by this Deployment.

pod/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyyThis is a pod created by the Replica Set.

Let's explain what these things are.

Pod

Can have one or multiple containers

Runs on a single node

(Pod cannot "straddle" multiple nodes)

Pods cannot be moved

(e.g. in case of node outage)

Pods cannot be scaled

(except by manually creating more Pods)

Pod details

A Pod is not a process; it's an environment for containers

it cannot be "restarted"

it cannot "crash"

The containers in a Pod can crash

They may or may not get restarted

(depending on Pod's restart policy)

If all containers exit successfully, the Pod ends in "Succeeded" phase

If some containers fail and don't get restarted, the Pod ends in "Failed" phase

Replica Set

Set of identical (replicated) Pods

Defined by a pod template + number of desired replicas

If there are not enough Pods, the Replica Set creates more

(e.g. in case of node outage; or simply when scaling up)

If there are too many Pods, the Replica Set deletes some

(e.g. if a node was disconnected and comes back; or when scaling down)

We can scale up/down a Replica Set

we update the manifest of the Replica Set

as a consequence, the Replica Set controller creates/deletes Pods

Deployment

Replica Sets control identical Pods

Deployments are used to roll out different Pods

(different image, command, environment variables, ...)

When we update a Deployment with a new Pod definition:

a new Replica Set is created with the new Pod definition

that new Replica Set is progressively scaled up

meanwhile, the old Replica Set(s) is(are) scaled down

This is a rolling update, minimizing application downtime

When we scale up/down a Deployment, it scales up/down its Replica Set

kubectl run through the ages

When we want to run an app on Kubernetes, we generally want a Deployment

Up to Kubernetes 1.17,

kubectl runcreated a Deploymentit could also create other things, by using special flags

this was powerful, but potentially confusing

creating a single Pod was done with

kubectl run --restart=Neverother resources could also be created with

kubectl create ...

From Kubernetes 1.18,

kubectl runcreates a Pod- other kinds of resources can still be created with

kubectl create

- other kinds of resources can still be created with

Creating a Deployment the proper way

Let's destroy that

pingpongapp that we createdThen we will use

kubectl create deploymentto re-create it

On Kubernetes 1.18+, delete the Pod named

pingpong:kubectl delete pod pingpongOn Kubernetes 1.17-, delete the Deployment named

pingpong:kubectl delete deployment pingpong

Running ping in a Deployment

When using

kubectl create deployment, we cannot indicate the command to execute(at least, not in Kubernetes 1.18; but that changed in Kubernetes 1.19)

We can:

- write a custom YAML manifest for our Deployment

Running ping in a Deployment

When using

kubectl create deployment, we cannot indicate the command to execute(at least, not in Kubernetes 1.18; but that changed in Kubernetes 1.19)

We can:

write a custom YAML manifest for our Deployment

(yeah right ... too soon!)

Running ping in a Deployment

When using

kubectl create deployment, we cannot indicate the command to execute(at least, not in Kubernetes 1.18; but that changed in Kubernetes 1.19)

We can:

write a custom YAML manifest for our Deployment

(yeah right ... too soon!)

use an image that has the command to execute baked in

(much easier!)

Running ping in a Deployment

When using

kubectl create deployment, we cannot indicate the command to execute(at least, not in Kubernetes 1.18; but that changed in Kubernetes 1.19)

We can:

write a custom YAML manifest for our Deployment

(yeah right ... too soon!)

use an image that has the command to execute baked in

(much easier!)

We will use the image

jpetazzo/ping(it has a default command of

ping 127.0.0.1)

Creating a Deployment running ping

Let's create a Deployment named

pingpongIt will use the image

jpetazzo/ping

Create the Deployment:

kubectl create deployment pingpong --image=jpetazzo/pingCheck the resources that were created:

kubectl get all

In Kubernetes 1.19

Since Kubernetes 1.19, we can specify the command to run

The command must be passed after two dashes:

kubectl create deployment pingpong --image=alpine -- ping 127.1

Viewing container output

Let's use the

kubectl logscommandWe will pass either a pod name, or a type/name

(E.g. if we specify a deployment or replica set, it will get the first pod in it)

Unless specified otherwise, it will only show logs of the first container in the pod

(Good thing there's only one in ours!)

- View the result of our

pingcommand:kubectl logs deploy/pingpong

Streaming logs in real time

Just like

docker logs,kubectl logssupports convenient options:-f/--followto stream logs in real time (à latail -f)--tailto indicate how many lines you want to see (from the end)--sinceto get logs only after a given timestamp

View the latest logs of our

pingcommand:kubectl logs deploy/pingpong --tail 1 --followStop it with Ctrl-C

Scaling our application

- We can create additional copies of our container (I mean, our pod) with

kubectl scale

Scale our

pingpongdeployment:kubectl scale deploy/pingpong --replicas 3Note that this command does exactly the same thing:

kubectl scale deployment pingpong --replicas 3Check that we now have multiple pods:

kubectl get pods

Scaling a Replica Set

What if we scale the Replica Set instead of the Deployment?

The Deployment would notice it right away and scale back to the initial level

The Replica Set makes sure that we have the right numbers of Pods

The Deployment makes sure that the Replica Set has the right size

(conceptually, it delegates the management of the Pods to the Replica Set)

This might seem weird (why this extra layer?) but will soon make sense

(when we will look at how rolling updates work!)

Streaming logs of multiple pods

- What happens if we try

kubectl logsnow that we have multiple pods?

kubectl logs deploy/pingpong --tail 3kubectl logs will warn us that multiple pods were found.

It is showing us only one of them.

We'll see later how to address that shortcoming.

Resilience

The deployment

pingpongwatches its replica setThe replica set ensures that the right number of pods are running

What happens if pods disappear?

- In a separate window, watch the list of pods:watch kubectl get pods

- Destroy the pod currently shown by

kubectl logs:kubectl delete pod pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy

What happened?

kubectl delete podterminates the pod gracefully(sending it the TERM signal and waiting for it to shutdown)

As soon as the pod is in "Terminating" state, the Replica Set replaces it

But we can still see the output of the "Terminating" pod in

kubectl logsUntil 30 seconds later, when the grace period expires

The pod is then killed, and

kubectl logsexits

:EN:- Running pods and deployments :FR:- Créer un pod et un déploiement

Executing batch jobs

(automatically generated title slide)

Executing batch jobs

Deployments are great for stateless web apps

(as well as workers that keep running forever)

Pods are great for one-off execution that we don't care about

(because they don't get automatically restarted if something goes wrong)

Jobs are great for "long" background work

("long" being at least minutes or hours)

CronJobs are great to schedule Jobs at regular intervals

(just like the classic UNIX

crondaemon with itscrontabfiles)

Creating a Job

A Job will create a Pod

If the Pod fails, the Job will create another one

The Job will keep trying until:

either a Pod succeeds,

or we hit the backoff limit of the Job (default=6)

- Create a Job that has a 50% chance of success:kubectl create job flipcoin --image=alpine -- sh -c 'exit $(($RANDOM%2))'

Our Job in action

Our Job will create a Pod named

flipcoin-xxxxxIf the Pod succeeds, the Job stops

If the Pod fails, the Job creates another Pod

- Check the status of the Pod(s) created by the Job:kubectl get pods --selector=job-name=flipcoin

More advanced jobs

We can specify a number of "completions" (default=1)

This indicates how many times the Job must be executed

We can specify the "parallelism" (default=1)

This indicates how many Pods should be running in parallel

These options cannot be specified with

kubectl create job(we have to write our own YAML manifest to use them)

Scheduling periodic background work

A Cron Job is a Job that will be executed at specific intervals

(the name comes from the traditional cronjobs executed by the UNIX crond)

It requires a schedule, represented as five space-separated fields:

- minute [0,59]

- hour [0,23]

- day of the month [1,31]

- month of the year [1,12]

- day of the week ([0,6] with 0=Sunday)

*means "all valid values";/Nmeans "every N"Example:

*/3 * * * *means "every three minutes"

Creating a Cron Job

Let's create a simple job to be executed every three minutes

Careful: make sure that the job terminates!

(The Cron Job will not hold if a previous job is still running)

Create the Cron Job:

kubectl create cronjob every3mins --schedule="*/3 * * * *" \--image=alpine -- sleep 10Check the resource that was created:

kubectl get cronjobs

Cron Jobs in action

At the specified schedule, the Cron Job will create a Job

The Job will create a Pod

The Job will make sure that the Pod completes

(re-creating another one if it fails, for instance if its node fails)

- Check the Jobs that are created:kubectl get jobs

(It will take a few minutes before the first job is scheduled.)

Setting a time limit

It is possible to set a time limit (or deadline) for a job

This is done with the field

spec.activeDeadlineSeconds(by default, it is unlimited)

When the job is older than this time limit, all its pods are terminated

Note that there can also be a

spec.activeDeadlineSecondsfield in pods!They can be set independently, and have different effects:

the deadline of the job will stop the entire job

the deadline of the pod will only stop an individual pod

What about kubectl run before v1.18?

Creating a Deployment:

kubectl runCreating a Pod:

kubectl run --restart=NeverCreating a Job:

kubectl run --restart=OnFailureCreating a Cron Job:

kubectl run --restart=OnFailure --schedule=...

Avoid using these forms, as they are deprecated since Kubernetes 1.18!

Beyond kubectl create

As hinted earlier,

kubectl createdoesn't always expose all optionscan't express parallelism or completions of Jobs

can't express healthchecks, resource limits

kubectl createandkubectl runare helpers that generate YAML manifestsIf we write these manifests ourselves, we can use all features and options

We'll see later how to do that!

:EN:- Running batch and cron jobs :FR:- Tâches périodiques (cron) et traitement par lots (batch)

Labels and annotations

(automatically generated title slide)

Labels and annotations

Most Kubernetes resources can have labels and annotations

Both labels and annotations are arbitrary strings

(with some limitations that we'll explain in a minute)

Both labels and annotations can be added, removed, changed, dynamically

This can be done with:

the

kubectl editcommandthe

kubectl labelandkubectl annotate... many other ways! (

kubectl apply -f,kubectl patch, ...)

Viewing labels and annotations

- Let's see what we get when we create a Deployment

Create a Deployment:

kubectl create deployment clock --image=jpetazzo/clockLook at its annotations and labels:

kubectl describe deployment clock

So, what do we get?

Labels and annotations for our Deployment

We see one label:

Labels: app=clockThis is added by

kubectl create deploymentAnd one annotation:

Annotations: deployment.kubernetes.io/revision: 1This is to keep track of successive versions when doing rolling updates

And for the related Pod?

- Let's look up the Pod that was created and check it too

Find the name of the Pod:

kubectl get podsDisplay its information:

kubectl describe pod clock-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy

So, what do we get?

Labels and annotations for our Pod

We see two labels:

Labels: app=clockpod-template-hash=xxxxxxxxxxapp=clockcomes fromkubectl create deploymenttoopod-template-hashwas assigned by the Replica Set(when we will do rolling updates, each set of Pods will have a different hash)

There are no annotations:

Annotations: <none>

Selectors

A selector is an expression matching labels

It will restrict a command to the objects matching at least all these labels

List all the pods with at least

app=clock:kubectl get pods --selector=app=clockList all the pods with a label

app, regardless of its value:kubectl get pods --selector=app

Settings labels and annotations

- The easiest method is to use

kubectl labelandkubectl annotate

Set a label on the

clockDeployment:kubectl label deployment clock color=blueCheck it out:

kubectl describe deployment clock

Other ways to view labels

kubectl getgives us a couple of useful flags to check labelskubectl get --show-labelsshows all labelskubectl get -L xyzshows the value of labelxyz

List all the labels that we have on pods:

kubectl get pods --show-labelsList the value of label

appon these pods:kubectl get pods -L app

More on selectors

If a selector has multiple labels, it means "match at least these labels"

Example:

--selector=app=frontend,release=prod--selectorcan be abbreviated as-l(for labels)We can also use negative selectors

Example:

--selector=app!=clockSelectors can be used with most

kubectlcommandsExamples:

kubectl delete,kubectl label, ...

Other ways to view labels

- We can use the

--show-labelsflag withkubectl get

- Show labels for a bunch of objects:kubectl get --show-labels po,rs,deploy,svc,no

Differences between labels and annotations

The key for both labels and annotations:

must start and end with a letter or digit

can also have

.-_(but not in first or last position)can be up to 63 characters, or 253 +

/+ 63

Label values are up to 63 characters, with the same restrictions

Annotations values can have arbitrary characters (yes, even binary)

Maximum length isn't defined

(dozens of kilobytes is fine, hundreds maybe not so much)

:EN:- Labels and annotations :FR:- Labels et annotations

Revisiting kubectl logs

(automatically generated title slide)

Revisiting kubectl logs

In this section, we assume that we have a Deployment with multiple Pods

(e.g.

pingpongthat we scaled to at least 3 pods)We will highlights some of the limitations of

kubectl logs

Streaming logs of multiple pods

- By default,

kubectl logsshows us the output of a single Pod

- Try to check the output of the Pods related to a Deployment:kubectl logs deploy/pingpong --tail 1 --follow

kubectl logs only shows us the logs of one of the Pods.

Viewing logs of multiple pods

When we specify a deployment name, only one single pod's logs are shown

We can view the logs of multiple pods by specifying a selector

If we check the pods created by the deployment, they all have the label

app=pingpong(this is just a default label that gets added when using

kubectl create deployment)

- View the last line of log from all pods with the

app=pingponglabel:kubectl logs -l app=pingpong --tail 1

Streaming logs of multiple pods

- Can we stream the logs of all our

pingpongpods?

- Combine

-land-fflags:kubectl logs -l app=pingpong --tail 1 -f

Note: combining -l and -f is only possible since Kubernetes 1.14!

Let's try to understand why ...

Streaming logs of many pods

- Let's see what happens if we try to stream the logs for more than 5 pods

Scale up our deployment:

kubectl scale deployment pingpong --replicas=8Stream the logs:

kubectl logs -l app=pingpong --tail 1 -f

We see a message like the following one:

error: you are attempting to follow 8 log streams,but maximum allowed concurency is 5,use --max-log-requests to increase the limitWhy can't we stream the logs of many pods?

kubectlopens one connection to the API server per podFor each pod, the API server opens one extra connection to the corresponding kubelet

If there are 1000 pods in our deployment, that's 1000 inbound + 1000 outbound connections on the API server

This could easily put a lot of stress on the API server

Prior Kubernetes 1.14, it was decided to not allow multiple connections

From Kubernetes 1.14, it is allowed, but limited to 5 connections

(this can be changed with

--max-log-requests)For more details about the rationale, see PR #67573

Shortcomings of kubectl logs

We don't see which pod sent which log line

If pods are restarted / replaced, the log stream stops

If new pods are added, we don't see their logs

To stream the logs of multiple pods, we need to write a selector

There are external tools to address these shortcomings

(e.g.: Stern)

kubectl logs -l ... --tail N

If we run this with Kubernetes 1.12, the last command shows multiple lines

This is a regression when

--tailis used together with-l/--selectorIt always shows the last 10 lines of output for each container

(instead of the number of lines specified on the command line)

The problem was fixed in Kubernetes 1.13

See #70554 for details.

:EN:- Viewing logs with "kubectl logs" :FR:- Consulter les logs avec "kubectl logs"

Accessing logs from the CLI

(automatically generated title slide)

Accessing logs from the CLI

The

kubectl logscommand has limitations:it cannot stream logs from multiple pods at a time

when showing logs from multiple pods, it mixes them all together

We are going to see how to do it better

Doing it manually

We could (if we were so inclined) write a program or script that would:

take a selector as an argument

enumerate all pods matching that selector (with

kubectl get -l ...)fork one

kubectl logs --follow ...command per containerannotate the logs (the output of each

kubectl logs ...process) with their originpreserve ordering by using

kubectl logs --timestamps ...and merge the output

Doing it manually

We could (if we were so inclined) write a program or script that would:

take a selector as an argument

enumerate all pods matching that selector (with

kubectl get -l ...)fork one

kubectl logs --follow ...command per containerannotate the logs (the output of each

kubectl logs ...process) with their originpreserve ordering by using

kubectl logs --timestamps ...and merge the output

We could do it, but thankfully, others did it for us already!

Stern

Stern is an open source project by Wercker.

From the README:

Stern allows you to tail multiple pods on Kubernetes and multiple containers within the pod. Each result is color coded for quicker debugging.

The query is a regular expression so the pod name can easily be filtered and you don't need to specify the exact id (for instance omitting the deployment id). If a pod is deleted it gets removed from tail and if a new pod is added it automatically gets tailed.

Exactly what we need!

Checking if Stern is installed

Run

stern(without arguments) to check if it's installed:$ sternTail multiple pods and containers from KubernetesUsage:stern pod-query [flags]If it's missing, let's see how to install it

Installing Stern

Stern is written in Go, and Go programs are usually shipped as a single binary

We just need to download that binary and put it in our

PATH!Binary releases are available here on GitHub

The following commands will install Stern on a Linux Intel 64 bit machine:

sudo curl -L -o /usr/local/bin/stern \https://github.com/wercker/stern/releases/download/1.11.0/stern_linux_amd64sudo chmod +x /usr/local/bin/sternOn macOS, we can also

brew install sternorsudo port install stern

Using Stern

There are two ways to specify the pods whose logs we want to see:

-lfollowed by a selector expression (like with manykubectlcommands)with a "pod query," i.e. a regex used to match pod names

These two ways can be combined if necessary

- View the logs for all the pingpong containers:stern pingpong

Stern convenient options

The

--tail Nflag shows the lastNlines for each container(Instead of showing the logs since the creation of the container)

The

-t/--timestampsflag shows timestampsThe

--all-namespacesflag is self-explanatory

- View what's up with the

weavesystem containers:stern --tail 1 --timestamps --all-namespaces weave

Using Stern with a selector

When specifying a selector, we can omit the value for a label

This will match all objects having that label (regardless of the value)

Everything created with

kubectl runhas a labelrunEverything created with

kubectl create deploymenthas a labelappWe can use that property to view the logs of all the pods created with

kubectl create deployment

- View the logs for all the things started with

kubectl create deployment:stern -l app

:EN:- Viewing pod logs from the CLI :FR:- Consulter les logs des pods depuis la CLI

Declarative vs imperative

(automatically generated title slide)

Declarative vs imperative

Our container orchestrator puts a very strong emphasis on being declarative

Declarative:

I would like a cup of tea.

Imperative:

Boil some water. Pour it in a teapot. Add tea leaves. Steep for a while. Serve in a cup.

Declarative vs imperative

Our container orchestrator puts a very strong emphasis on being declarative

Declarative:

I would like a cup of tea.

Imperative:

Boil some water. Pour it in a teapot. Add tea leaves. Steep for a while. Serve in a cup.

Declarative seems simpler at first ...

Declarative vs imperative

Our container orchestrator puts a very strong emphasis on being declarative

Declarative:

I would like a cup of tea.

Imperative:

Boil some water. Pour it in a teapot. Add tea leaves. Steep for a while. Serve in a cup.

Declarative seems simpler at first ...

... As long as you know how to brew tea

Declarative vs imperative

What declarative would really be:

I want a cup of tea, obtained by pouring an infusion¹ of tea leaves in a cup.

Declarative vs imperative

What declarative would really be:

I want a cup of tea, obtained by pouring an infusion¹ of tea leaves in a cup.

¹An infusion is obtained by letting the object steep a few minutes in hot² water.

Declarative vs imperative

What declarative would really be:

I want a cup of tea, obtained by pouring an infusion¹ of tea leaves in a cup.

¹An infusion is obtained by letting the object steep a few minutes in hot² water.

²Hot liquid is obtained by pouring it in an appropriate container³ and setting it on a stove.

Declarative vs imperative

What declarative would really be:

I want a cup of tea, obtained by pouring an infusion¹ of tea leaves in a cup.

¹An infusion is obtained by letting the object steep a few minutes in hot² water.

²Hot liquid is obtained by pouring it in an appropriate container³ and setting it on a stove.

³Ah, finally, containers! Something we know about. Let's get to work, shall we?

Declarative vs imperative

What declarative would really be:

I want a cup of tea, obtained by pouring an infusion¹ of tea leaves in a cup.

¹An infusion is obtained by letting the object steep a few minutes in hot² water.

²Hot liquid is obtained by pouring it in an appropriate container³ and setting it on a stove.

³Ah, finally, containers! Something we know about. Let's get to work, shall we?

Did you know there was an ISO standard specifying how to brew tea?

Declarative vs imperative

Imperative systems:

simpler

if a task is interrupted, we have to restart from scratch

Declarative systems:

if a task is interrupted (or if we show up to the party half-way through), we can figure out what's missing and do only what's necessary

we need to be able to observe the system

... and compute a "diff" between what we have and what we want

Declarative vs imperative in Kubernetes

With Kubernetes, we cannot say: "run this container"

All we can do is write a spec and push it to the API server

(by creating a resource like e.g. a Pod or a Deployment)

The API server will validate that spec (and reject it if it's invalid)

Then it will store it in etcd

A controller will "notice" that spec and act upon it

Reconciling state

Watch for the

specfields in the YAML files later!The spec describes how we want the thing to be

Kubernetes will reconcile the current state with the spec

(technically, this is done by a number of controllers)When we want to change some resource, we update the spec

Kubernetes will then converge that resource

:EN:- Declarative vs imperative models :FR:- Modèles déclaratifs et impératifs

19,000 words

They say, "a picture is worth one thousand words."

The following 19 slides show what really happens when we run:

kubectl create deployment web --image=nginxKubernetes network model

(automatically generated title slide)

Kubernetes network model

TL,DR:

Our cluster (nodes and pods) is one big flat IP network.

Kubernetes network model

TL,DR:

Our cluster (nodes and pods) is one big flat IP network.

In detail:

all nodes must be able to reach each other, without NAT

all pods must be able to reach each other, without NAT

pods and nodes must be able to reach each other, without NAT

each pod is aware of its IP address (no NAT)

pod IP addresses are assigned by the network implementation

Kubernetes doesn't mandate any particular implementation

Kubernetes network model: the good

Everything can reach everything

No address translation

No port translation

No new protocol

The network implementation can decide how to allocate addresses

IP addresses don't have to be "portable" from a node to another

(We can use e.g. a subnet per node and use a simple routed topology)

The specification is simple enough to allow many various implementations

Kubernetes network model: the less good

Everything can reach everything

if you want security, you need to add network policies

the network implementation that you use needs to support them

There are literally dozens of implementations out there

(https://github.com/containernetworking/cni/ lists more than 25 plugins)

Pods have level 3 (IP) connectivity, but services are level 4 (TCP or UDP)

(Services map to a single UDP or TCP port; no port ranges or arbitrary IP packets)

kube-proxyis on the data path when connecting to a pod or container,

and it's not particularly fast (relies on userland proxying or iptables)

Kubernetes network model: in practice

The nodes that we are using have been set up to use Weave

We don't endorse Weave in a particular way, it just Works For Us

Don't worry about the warning about

kube-proxyperformanceUnless you:

- routinely saturate 10G network interfaces

- count packet rates in millions per second

- run high-traffic VOIP or gaming platforms

- do weird things that involve millions of simultaneous connections

(in which case you're already familiar with kernel tuning)

If necessary, there are alternatives to

kube-proxy; e.g.kube-router

The Container Network Interface (CNI)

Most Kubernetes clusters use CNI "plugins" to implement networking

When a pod is created, Kubernetes delegates the network setup to these plugins

(it can be a single plugin, or a combination of plugins, each doing one task)

Typically, CNI plugins will:

allocate an IP address (by calling an IPAM plugin)

add a network interface into the pod's network namespace

configure the interface as well as required routes etc.

Multiple moving parts

The "pod-to-pod network" or "pod network":

provides communication between pods and nodes

is generally implemented with CNI plugins

The "pod-to-service network":

provides internal communication and load balancing

is generally implemented with kube-proxy (or e.g. kube-router)

Network policies:

provide firewalling and isolation

can be bundled with the "pod network" or provided by another component

Even more moving parts

Inbound traffic can be handled by multiple components:

something like kube-proxy or kube-router (for NodePort services)

load balancers (ideally, connected to the pod network)

It is possible to use multiple pod networks in parallel

(with "meta-plugins" like CNI-Genie or Multus)

Some solutions can fill multiple roles

(e.g. kube-router can be set up to provide the pod network and/or network policies and/or replace kube-proxy)

:EN:- The Kubernetes network model :FR:- Le modèle réseau de Kubernetes

Exposing containers

(automatically generated title slide)

Exposing containers

We can connect to our pods using their IP address

Then we need to figure out a lot of things:

how do we look up the IP address of the pod(s)?

how do we connect from outside the cluster?

how do we load balance traffic?

what if a pod fails?

Kubernetes has a resource type named Service

Services address all these questions!

Services in a nutshell

Services give us a stable endpoint to connect to a pod or a group of pods

An easy way to create a service is to use

kubectl exposeIf we have a deployment named

my-little-deploy, we can run:kubectl expose deployment my-little-deploy --port=80... and this will create a service with the same name (

my-little-deploy)Services are automatically added to an internal DNS zone

(in the example above, our code can now connect to http://my-little-deploy/)

Advantages of services

We don't need to look up the IP address of the pod(s)

(we resolve the IP address of the service using DNS)

There are multiple service types; some of them allow external traffic

(e.g.

LoadBalancerandNodePort)Services provide load balancing

(for both internal and external traffic)

Service addresses are independent from pods' addresses

(when a pod fails, the service seamlessly sends traffic to its replacement)

Many kinds and flavors of service

There are different types of services:

ClusterIP,NodePort,LoadBalancer,ExternalNameThere are also headless services

Services can also have optional external IPs

There is also another resource type called Ingress

(specifically for HTTP services)

Wow, that's a lot! Let's start with the basics ...

ClusterIP

It's the default service type

A virtual IP address is allocated for the service

(in an internal, private range; e.g. 10.96.0.0/12)

This IP address is reachable only from within the cluster (nodes and pods)

Our code can connect to the service using the original port number

Perfect for internal communication, within the cluster

LoadBalancer

An external load balancer is allocated for the service

(typically a cloud load balancer, e.g. ELB on AWS, GLB on GCE ...)

This is available only when the underlying infrastructure provides some kind of "load balancer as a service"

Each service of that type will typically cost a little bit of money

(e.g. a few cents per hour on AWS or GCE)

Ideally, traffic would flow directly from the load balancer to the pods

In practice, it will often flow through a

NodePortfirst

NodePort

A port number is allocated for the service

(by default, in the 30000-32767 range)

That port is made available on all our nodes and anybody can connect to it

(we can connect to any node on that port to reach the service)

Our code needs to be changed to connect to that new port number

Under the hood:

kube-proxysets up a bunch ofiptablesrules on our nodesSometimes, it's the only available option for external traffic